After answering our questions on the subject of “preventive health care,” Professor Christoph Bamberger answers our questions about stress management in this interview.

Professor Bamberger is an internal medicine specialist and endocrinologist. He runs the Conradia Medical Prevention Center in Hamburg, where stress management is part of the health check-up. Professor Bamberger has already published many books on various health topics, including several publications on intelligent stress management.

Dear Professor Bamberger, thank you very much for taking the time again to do an interview with us. Today we will be talking about stress management. It is well known that “stress makes you sick”. What happens in the body when we are stressed?

Yes, very much so. Perhaps first of all: stress is a completely natural response of the body to real or imagined stressors, i.e. stress triggers. If we had no stress response at all, we would not be able to survive. We would not be able to react adequately in many situations. A distinction is made between external and internal stressors. External stressors are stimuli that result from the actual external environment. A typical external stressor in a professional context is a deadline that is impossible or difficult to meet. Internal stressors are stimuli that are individually perceived as stressful. This can be due to one’s own demands, one’s own perception or even general fears.

But regardless of whether it is real or imagined, the brain does not care, it always reacts with a stress response. From the brain, the stress reaction goes through the nervous system and the hormone system into the body. In the nervous system, this happens mainly through the release of adrenaline, which is the so-called “acute stress reaction“. This was devised by nature so that in a dangerous situation we can either run away quickly or fight (= “fight or flight” response). Here, blood pressure is increased and blood sugar is made available. Energy is thus mobilized so that we can face the confrontation. We have such a stress reaction in all kinds of situations, even in traffic. This can hardly be avoided, but it is not a bad thing every now and then.

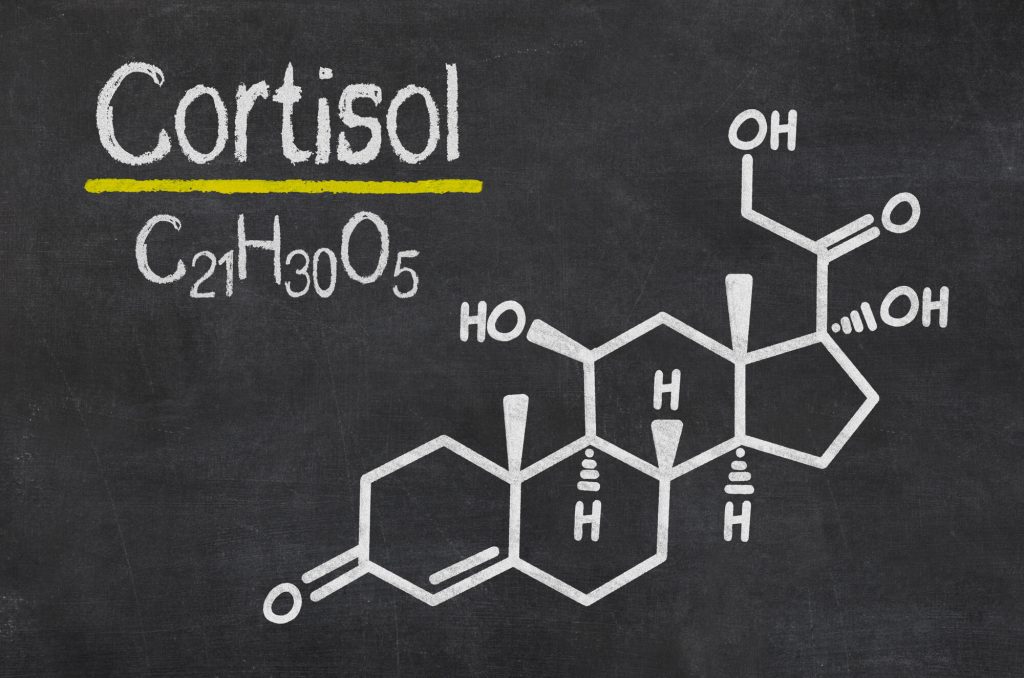

However, if a stressor does not go away, e.g. a professional conflict persists for months at the workplace, then the famous “chronic stress” develops. This no longer has anything to do with adrenaline. Chronic stress is mediated by the much longer-acting cortisol, the stress hormone from the adrenal cortex. And this is the stress that makes us sick. Cortisol, as the name implies, is like cortisone in terms of its effect. And we all know what a person looks like and how they feel when they’re given high doses of cortisone over a long period of time. Someone like that often struggles with weight gain, their skin gets thinner, they have bleeding, they get diabetes, and they get high blood pressure. And these again are factors that, if the phase goes on for a long time, lead to heart attacks and strokes. That, in a nutshell, is the mechanism by which chronic stress makes us sick.

At what point do you speak of chronic stress?

The cortisol comes in after several days, but it doesn’t do any real damage until after 3 months. So with any stress phase lasting more than 3 months, you should think about how to get out of it and what you can do to switch off. These 3 months are a somewhat contrived limit, but they correspond – in our experience – to the point at which many problems begin.

But surely there are also individual limits or resilience levels, aren’t there? How do I recognize that I am under too much stress?

I can tell by the fact that physical symptoms appear. That is, when you don’t just feel stressed, but the organ that reacts most sensitively to stress sends signals. For some people it’s the intestines, for others it’s back pain. Then there are people who get difficulties with high blood pressure and others who struggle with headaches and sleep disorders. These types of reactions should be a clear red flag. It’s at this point, at the very latest, that one should act. If one ignores these bodily reactions over a longer period, then a burnout is imminent. In this case, cortisol production is no longer sufficient and a so-called “low cortisol state” is reached. The burnout is the late stage, which should and also does not have to be reached. There is no one who feels only chronically stressed, but who is completely well physically.

Do you notice that certain groups of people are particularly at risk of stress? Does it tend to be the executive manager who is busy at work or rather the single mother?

Yes, that’s a good question. For one thing, it depends on what you consider natural and what you don’t. The single mother perceives her tasks as right and as important. She is willing to do anything for her child. This sense of purpose may be missing in the manager who has already worked 18 hours and still believes he will not meet a deadline. In addition to this feeling of meaninglessness and being overwhelmed, there may also be the fear of being fired for not delivering on the job. We often observe chronic stress in managers who are in a sandwich position, i.e. who are under pressure from above and below. Owners of medium-sized companies also often have existential fears, resulting from a non-functioning of the company or even a special event such as a flood disaster or similar. These are stressors that cannot simply be explained away.

What can you do then? What stress killers work for most people?

I have written a book called “Stressintelligenz” (English: “Stress Intelligence”). In this book I outline three steps.

The first step is to identify and reduce your stressors. You should sit down and think about which stressors you can kick out. We encounter many stressors every day. Already the way to work contains stress for many people. We should also get rid of meetings that only make the day fuller and more strenuous without bringing anything to the table. The same applies to the private sphere. Here one should ask oneself, “Which encounters really add value to my life?” Some stressors, of course, cannot be sorted out, especially in a professional context. But there may be a professional constellation that is not so enormously stressful.

The second step is to build resilience, which is the idea of making the body more resistant. I need a kind of armor against the stressors that remain. Physical activity in the form of sports, for example, leads to an enormous reduction in stress. You could resolve to go for a 5 km walk every day from now on or to do a sport that you enjoy. A healthy diet is also very important in this context.

The third step is to make the psyche more resistant. One should find an individually suitable method to be able to actively shut down at any time. Spirituality helps some people. Other people, who are more rational, do well with autogenic training or relaxing audio books.

How important is a good night’s sleep in this context?

The importance of a good night’s sleep cannot be underestimated. It is clearly a sacred thing in prevention. Of course, it is important that – if you are one of the somewhat lighter sleepers – you do not claim to reach a certain number like 7 or 8 hours. This is always repeated like a prayer mill, but it’s not that simple. It’s primarily about feeling refreshed in the morning. If 5 hours is enough, you don’t have to force yourself to sleep longer. But most people need 7 hours of sleep already. Sleep is the relaxation method that is superior to all others. Even the power nap at noon can bring a lot of relaxation. But this, by the way, should not take place after 3 pm and should not last longer than half an hour. Otherwise, night sleep will be disturbed. So if I were to categorize the effect of sleep on stress management into “important, unimportant, moderately important”, then I can only say “extremely important”.